Added Value and Human Rights

Cocoa and the Economics of Global Inequity

Abstract

The denial of “added value” lies at the core of global economic inequity and its human rights consequences. While underdeveloped countries supply the raw materials that fuel global industries, developed economies capture the real wealth by processing, branding, and selling finished goods. Cocoa is a striking example: West Africa produces most of the world’s cocoa beans, yet farmers earn poverty wages while multinational chocolate companies reap billions in profits. This inequity sustains child labor, denies the right to education, entrenches poverty, and fuels migration. International human rights law recognizes the rights to work, to an adequate standard of living, and to self-determination over natural resources. Yet global trade practices continue to violate these rights by preventing producing countries from sharing in the added value of their own resources. Fairer trade and production systems that respect human rights are essential to dismantling structural inequities and creating global stability.

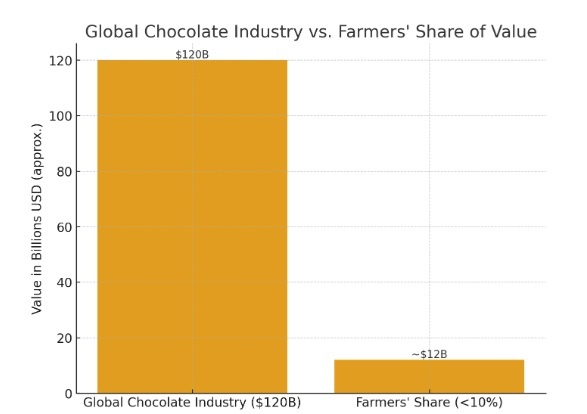

In economics, “added value” refers to the increase in worth created when a raw material is transformed into a finished product. A commodity such as cocoa beans may be cheap in its raw form, but once it is roasted, blended, packaged, and branded, it becomes part of a global chocolate industry worth over $120 billion annually. The control over who gets to add that value—and thus capture the wealth it generates—largely determines which societies prosper and which remain in poverty.

The case of cocoa shows the stark injustice of this arrangement. Côte d’Ivoire and Ghana together produce nearly 60 percent of the world’s cocoa beans, yet the farmers who grow them earn less than 10 percent of the final retail price of chocolate. According to Fairtrade International, most cocoa farmers survive on under $1.50 a day, below the World Bank’s poverty threshold. Meanwhile, multinational chocolate corporations headquartered in Europe and North America post annual profits in the billions. The imbalance is not just economic; it translates into widespread human rights violations.

Because cocoa farming pays so little, families rely on child labor to survive. The U.S. Department of Labor estimates that more than 1.5 million children in Ghana and Côte d’Ivoire are engaged in child labor in cocoa production, many exposed to hazardous conditions including pesticide use and heavy physical work. Poverty wages mean children are pulled from school, undermining their right to education. Families lack access to adequate housing, healthcare, and nutrition, denying them the right to an adequate standard of living. These are not abstract violations—they are lived realities directly tied to a global system that denies producing countries the right to capture added value from their own resources.

The human rights framework provides a powerful lens for understanding this injustice. The International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights (ICESCR) affirms the rights to work under just and favorable conditions, to education, to an adequate standard of living, and to the continuous improvement of living conditions. It also enshrines the right of all peoples to freely dispose of their natural wealth and resources. Yet in practice, trade rules and corporate practices ensure that while West African nations supply the raw cocoa, the real wealth and industrial growth are captured abroad. This is not just a market outcome; it is a systematic denial of rights recognized in international law.

The human rights framework provides a powerful lens for understanding this injustice. The International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights (ICESCR) affirms the rights to work under just and favorable conditions, to education, to an adequate standard of living, and to the continuous improvement of living conditions. It also enshrines the right of all peoples to freely dispose of their natural wealth and resources. Yet in practice, trade rules and corporate practices ensure that while West African nations supply the raw cocoa, the real wealth and industrial growth are captured abroad. This is not just a market outcome; it is a systematic denial of rights recognized in international law.

The inequity extends far beyond cocoa. Similar patterns mark the trade in coffee, cobalt, and cotton, where farmers and miners in the Global South capture only a sliver of the value chain while developed economies dominate the profitable sectors of refining, branding, and distribution. The persistence of this model perpetuates poverty, drives migration, and destabilizes communities. It is no coincidence that the same wealthy countries that resist migration inflows are those whose trade practices undermine the livelihoods that would allow people to remain at home with dignity.

Calls for “America First” or “UK First” policies reveal the hypocrisy at the heart of the system. When powerful nations demand that production and jobs stay within their borders, they recognize the importance of capturing added value for national prosperity. Yet when Ghana or Côte d’Ivoire attempt to require more local chocolate production, or when the Democratic Republic of Congo seeks to refine cobalt domestically, they are met with resistance from multinational corporations and pressure from international financial institutions. The right to added value, it seems, is reserved for the powerful.

A fairer system would extend this principle universally. Producing countries must be able to process and market their own resources, creating industries, jobs, and tax bases that uphold human rights and ensure dignity. This is not a call to end trade, but to rebalance it so that prosperity circulates more equitably and the rights of all peoples are respected. Recognizing the right to added value is inseparable from recognizing fundamental human rights.

Until then, every bar of chocolate carries with it not only sweetness but also the bitter taste of inequity and human rights denied.