Nations’ Borrowing from the Future Betrays the Basic Norms of Rights

Abstract:

National debt is often framed as an economic necessity—a tool for growth, stability, and strategic investment. Yet history reveals that debt has also been a recurring instrument of decline, eroding empires, undermining sovereignty, and transferring the cost of ambition onto future generations. This essay argues that public debt must be understood not only in fiscal terms but as a profound human rights issue. When states borrow beyond their means, they bind people who do not yet exist to obligations they never consented to—effectively transforming unborn generations into economic subjects without voice or agency. Drawing on historical examples and contemporary data from the world’s most indebted nations, the essay traces how unsustainable borrowing constrains development, deepens inequality, and compromises the capacity of future societies to uphold basic human dignity. It calls for a reimagining of fiscal responsibility as moral responsibility: a recognition that debt, when misused, is not just a financial burden but a form of intergenerational injustice—a silent exploitation of the future by the present.

Throughout history, national debt has been both a tool of power and a moral test. Empires and states have borrowed to build roads, wage wars, and fund revolutions—but also to delay responsibility, to push the burden of today’s ambitions onto tomorrow’s citizens. When governments treat debt as an instrument of control or a source of artificial prosperity, they are not merely taking on financial obligations. They are borrowing against time, against the lives and possibilities of people not yet born.

In that sense, debt is not only an economic issue—it is a human rights issue. Every loan contract signed by a state binds not only its current citizens but generations who had no voice in the decision. Future generations cannot vote, protest, or negotiate the terms of the debt that will define their opportunities. Yet, they will inherit its consequences: reduced public services, lower growth, environmental degradation, and diminished sovereignty. When debt becomes excessive, it transforms from a financial instrument into a form of intergenerational exploitation.

History provides ample warning. From ancient city-states to modern superpowers, the collapse of heavily indebted societies follows a familiar script: borrowed money fuels expansion and excess, but when growth slows or confidence fades, debt becomes a chain. Spain in the sixteenth century, awash in silver from the New World, financed endless wars through credit—then defaulted, leaving future generations impoverished. The Ottoman Empire’s nineteenth-century borrowing led to foreign financial control that hollowed out its independence. Even in modern democracies, where debt may be approved by elected representatives, the question remains: who consents on behalf of those who will live with its burden decades later?

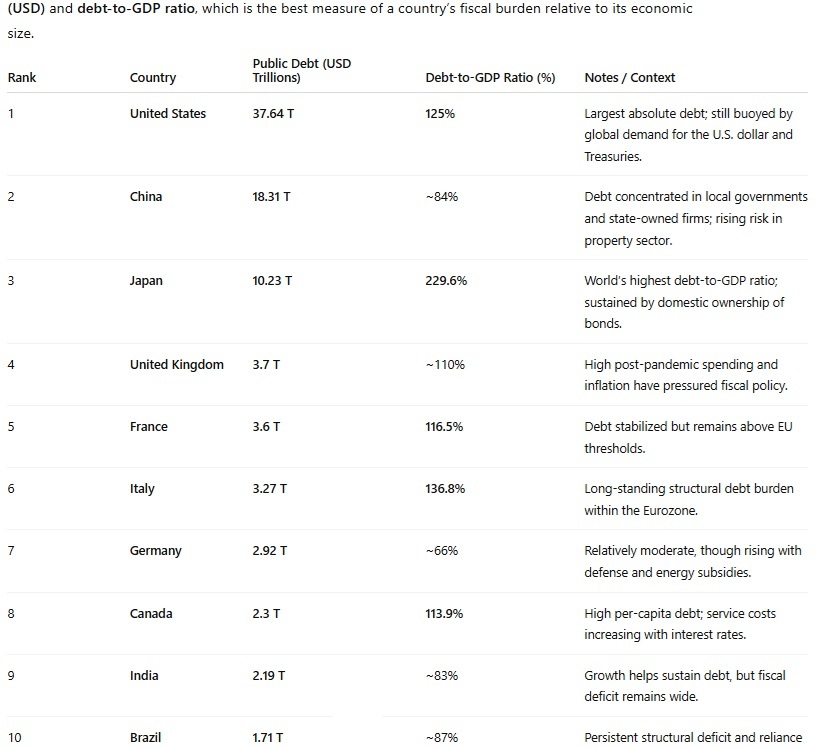

Today, the scale of global indebtedness is staggering. The United States leads the world with over $37 trillion in public debt. China owes about $18 trillion, Japan over $10 trillion, and major European economies follow with trillions more. When measured against the size of their economies, Japan’s debt stands at 229% of GDP, Sudan’s at 221%, Greece’s at 146%, and the United States at 125%. These figures are more than abstractions—they represent claims on the future income, labor, and welfare of citizens not yet born.

High debt ratios mean that more of tomorrow’s taxes will go not to education, healthcare, or climate adaptation, but to paying interest on decisions made today. In many developing nations, this translates into generations trapped in austerity and dependency—where governments spend more servicing old loans than investing in their people. In wealthier states, it constrains the ability to respond to crises, to innovate, or to ensure that social protections remain viable for those yet to come. Debt crowds out not just investment, but imagination.

The moral dimension deepens when we consider how debt intersects with inequality. Governments often justify borrowing as a way to preserve stability or fund social welfare. Yet when debt spirals, austerity measures tend to hit the most vulnerable first—cutting education, healthcare, and public goods that sustain human dignity. Thus, the rights of current citizens are also diminished, while future citizens are denied even the possibility of a just inheritance. The wealthy often benefit from debt-fueled markets; the poor pay the price when the bill comes due.

Seen in this light, fiscal irresponsibility becomes a quiet form of injustice. Borrowing beyond sustainable limits without democratic accountability is a violation of the social contract across time. The unborn cannot speak in parliament or protest in the streets, yet they are conscripted into repayment. They will live in the world shaped by our choices—its debts, its climate, its opportunities or their absence. To borrow recklessly, knowing that others will have to repay, is to treat the future not as a shared trust but as collateral.

To frame debt as a human rights issue is not poetic exaggeration; it is a necessary reframing. Economic policy is moral policy. When governments expand debt to finance consumption rather than sustainable growth, they erode the rights of those yet to come to live in societies capable of providing for them. Human rights are, at their core, about dignity, agency, and the freedom to shape one’s life. Debt that forecloses these freedoms for the next generation is a form of disenfranchisement.

History shows that debt crises often end not only in default but in disillusionment—when citizens lose faith that the state exists to protect their future. The question now facing indebted nations is not merely how much they owe, but to whom they owe moral responsibility. If the present continues to borrow from the future, we risk creating a world in which prosperity is always paid for by those who never consented to the bargain.

A just society must therefore see fiscal responsibility as part of its human rights framework. To live within one’s means is not only a matter of economics but of ethics—a recognition that the future is not ours to spend, but ours to preserve.