The Foundation of All Rights

Freedom of Speech

Abstract

Freedom of speech, thought, and conscience constitute the cornerstone of all human rights. Without the capacity to articulate claims, challenge authority, and bring grievances into the public sphere, other rights remain inaccessible and unenforceable. Drawing on the ideas presented in Muslims and the Western Conception of Rights , this essay argues that freedom of speech must be understood relationally, within the dynamics of power. The protection of vulnerable voices is paramount, while the claims of those with systemic power must be subject to limitation. Historical precedents demonstrate that transformative change has been initiated by the speech of the marginalized, underscoring the necessity of safeguarding this freedom as foundational to justice and human dignity.

The discourse on human rights presupposes the ability of individuals and communities to make claims against authority. Yet claims are not self-executing; they require articulation, dissemination, and recognition. As argued in Muslims and the Western Conception of Rights, the right that enables these processes—freedom of speech—is therefore not simply one right among many but the very foundation upon which all other rights depend. Absent this freedom, no individual or community can effectively assert their humanity or contest violations of dignity.

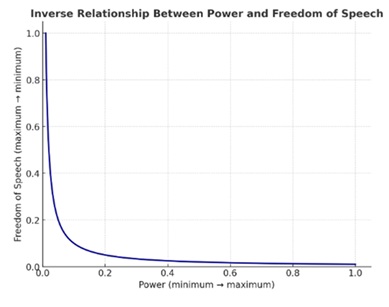

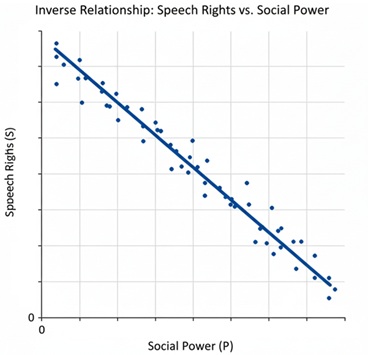

The indispensability of freedom of speech is most evident when examined through the prism of power. Rights are always situated in asymmetrical relationships. Individuals and groups with political authority, economic wealth, or social capital enjoy disproportionate access to platforms of communication and to the means of amplifying their voices. By contrast, marginalized communities often struggle to be heard. If freedom of speech is treated as an absolute, universal entitlement without consideration of these dynamics, it risks serving as a tool for consolidating privilege rather than as an instrument of justice.

The indispensability of freedom of speech is most evident when examined through the prism of power. Rights are always situated in asymmetrical relationships. Individuals and groups with political authority, economic wealth, or social capital enjoy disproportionate access to platforms of communication and to the means of amplifying their voices. By contrast, marginalized communities often struggle to be heard. If freedom of speech is treated as an absolute, universal entitlement without consideration of these dynamics, it risks serving as a tool for consolidating privilege rather than as an instrument of justice.

This recognition demands a relational understanding of the right to speech. Those with concentrated power—states, governments, large corporations, and media institutions—cannot be granted unqualified claims to speech, for their voices already shape and dominate the public sphere. Indeed, rights can become “tools of control” when they are framed without regard to inequality and hierarchy. The exercise of unrestrained speech by such actors functions to suppress dissent and marginalize alternative perspectives. Conversely, those with little or no structural power—workers, minorities, dissidents, and impoverished communities—require the broadest possible protection. For them, freedom of speech must approach the absolute, since it is their only effective means of making rights claims.

Speech, however, is rarely neutral. It emerges within contested terrains, where claims of expression can appear to one party as expressions of identity and to another as threats or injuries. Simplistic formulations, such as the assertion that “everyone has equal and absolute rights to speech,” obscure these complexities. They also perpetuate inequalities, as the already powerful are better positioned to exercise such rights. A more holistic approach must therefore be adopted, one that attends not only to the formal entitlement to speak but also to the material and social conditions that enable or constrain actual speech.

Historical experience reinforces this claim. Moments of profound transformation have not originated from the pronouncements of rulers or elites but from the speech of the vulnerable. The prophetic voices of Jesus and Muhammad challenged entrenched powers and inspired new moral orders despite their lack of worldly authority. Similarly, the modern struggles for civil rights, decolonization, and indigenous sovereignty were ignited by individuals and communities whose only power was the courage to speak. History offers numerous examples of individuals with little institutional power whose words challenged entrenched norms and provoked outrage from dominant groups, yet proved essential for social transformation. Socrates questioned the moral authority of Athenian democracy and was executed for impiety and corruption of the youth, yet his dialogues reshaped the course of philosophy. Martin Luther, an obscure monk, denounced the sale of indulgences and the authority of the Church hierarchy—positions considered heretical and dangerously subversive—igniting the Protestant Reformation. Galileo Galilei’s defense of heliocentrism contradicted established Church doctrine, leading to his trial and silencing, though his words eventually transformed science. In more recent times, Mary Wollstonecraft scandalized eighteenth-century Britain by declaring that women should enjoy the same rational and political rights as men, an assertion dismissed as unnatural and offensive by her contemporaries but foundational to modern feminism. Similarly, Frederick Douglass, once enslaved, shocked American society by exposing the brutality of slavery in speeches that many white audiences considered inflammatory and destabilizing. In the twentieth century, Nelson Mandela and Desmond Tutu denounced apartheid at great personal cost, initially branded as agitators and traitors by a system that relied on silencing dissent. These examples demonstrate a recurring historical truth: speech that unsettles the majority and affronts prevailing norms is the very speech that propels humanity toward greater justice. These examples underscore a critical truth: the advancement of justice depends on protecting the speech of the least powerful. Denying them this freedom not only perpetuates injustice but forecloses the possibility of meaningful change.

The conclusion follows directly: freedom of speech, thought, and conscience is the first among rights. It must be protected unconditionally for the powerless, whose voices are most at risk of suppression, and it must be limited for the powerful, whose influence otherwise overwhelms the public sphere. Framed in this way, freedom of speech is not a neutral entitlement but a principle of justice, safeguarding dignity by ensuring that even the most vulnerable retain the capacity to articulate their humanity.

Ultimately, the protection of freedom of speech sustains the very possibility of rights discourse. It enables critique, contestation, and transformation, without which the language of rights becomes hollow. To defend this freedom, particularly for those least able to defend themselves, is to preserve the integrity of human rights as a whole. It is for this reason that freedom of speech, thought, and conscience must be recognized as the cornerstone of human dignity and the indispensable foundation of justice.

In practical terms, a dynamic application of freedom of speech requires judicial and institutional mechanisms that differentiate between the speech of the powerful and the speech of the powerless. For instance, when a president with authoritarian tendencies seeks to curtail dissent, courts committed to a relational understanding of rights must categorically deny the executive branch any authority to restrict the speech of vulnerable individuals or groups. Such judicial restraint prevents those in power from weaponizing state institutions against dissenters and ensures that the speech of the marginalized retains absolute protection. Conversely, the same principle requires that authoritarians cannot themselves invoke freedom of speech as a shield for irresponsible or incendiary statements. Unlike the powerless individual whose speech may be offensive but carries little structural impact, the words of a president or government official are magnified by the machinery of the State. When such speech legitimizes violence, undermines institutions, or targets vulnerable populations, its potential harm far exceeds that of any utterance by an ordinary citizen. For this reason, absolute immunity of speech rights must always be guaranteed to those with little or no power, while no comparable immunity should be extended to entities such as the state and its agents, whose near-absolute power makes their speech categorically different.

Admittedly, this interpretation of free speech remains contested by the way governance and social systems are presently organized. Modern societies largely operate through rule-based or ideology-based systems, where law and policy are either reduced to technical compliance with codified rules or subordinated to the interests of prevailing ideological projects. In such contexts, freedom of speech risks being hollow, either confined within bureaucratic procedures or weaponized in service of partisan ends. For free speech to become a lived reality rather than an abstract entitlement, societies must transition towards principle-based systems, where fairness, justice, and dignity act as the primary drivers of governance. Principles provide the flexibility and normative compass necessary to respond to changing social realities without sacrificing the moral core of rights. By grounding governance in principles rather than rigid rules or entrenched ideologies a dynamic, adaptable framework for the protection of fundamental rights, especially free speech, can be secured.